Everyone loves democracy.

Do the test. In front of an audience, say “If you appreciate living in a democracy, raise your hand”, and you’ll get a forest of raised arms.

But right after, ask “If you think the democracy you live in is working well, raise your hand”. Shall we take bets? You’ll have no one left.

And when you think about it, it’s kind of crazy that something that works so poorly can still appeal to so many people. It’s downright paradoxical, so let’s give it a name:

The democratic paradox ™

So we wanted to dig deeper and ask people why they like democracy, and what comes up most often is that democracy is “fair”.

And when asked why their democracy malfunctions, it’s an avalanche: elected representatives don’t listen to citizens, don’t keep their promises, are corrupt, incompetent, hypocritical, haughty, out of touch with reality, too flexible, too rigid. Their decisions are stupid, thoughtless, hasty, waste public money, and lead to protests, demonstrations, strikes and sometimes riots.

So I have good news and bad news.

The good news is that, despite this vision of apocalypse, citizens remain attached to the idea of democracy. In France, 83% of people do, and that’s something of a miracle.

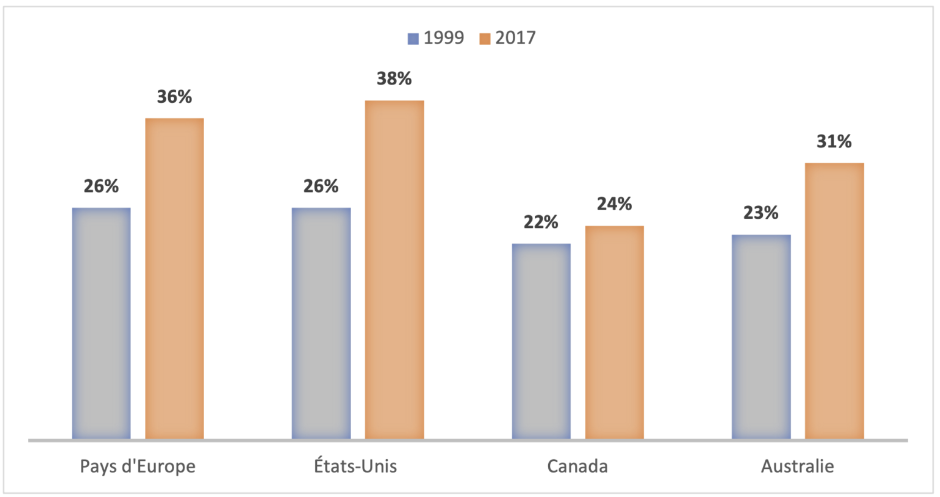

The bad news is that the remaining 17% think the whole thing would work a lot better if we handed all the power over to a little mustachioed guy who talks really loud and solves all the problems. And the bad news within the bad news is that, the way things are going, there are more and more of them.

(Source: World Value Survey and European Value Survey)

And then it really starts to suck, since we usually know how it ends.

It’s high time we understood what’s going wrong and why we’ve reached this point.

Why democracy used to work better (and now, not so well)

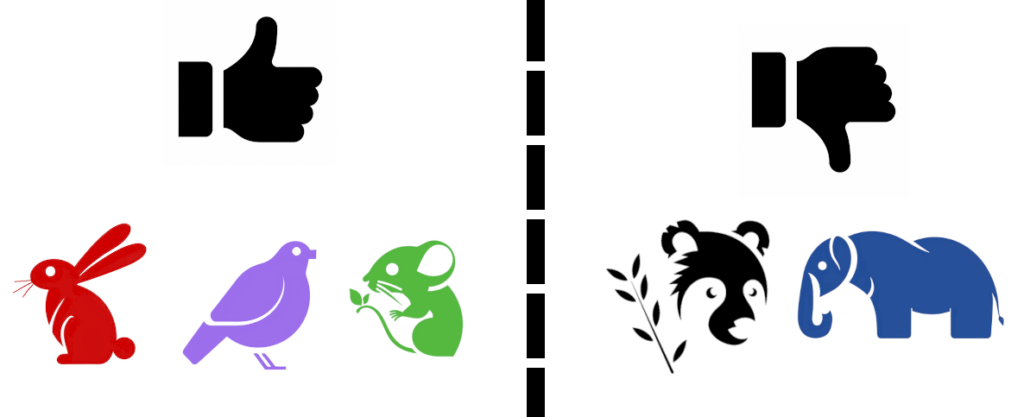

To illustrate this (and so as not to upset anyone), let’s transport ourselves for a moment to a world where all the animals on Earth live in a happy democracy.

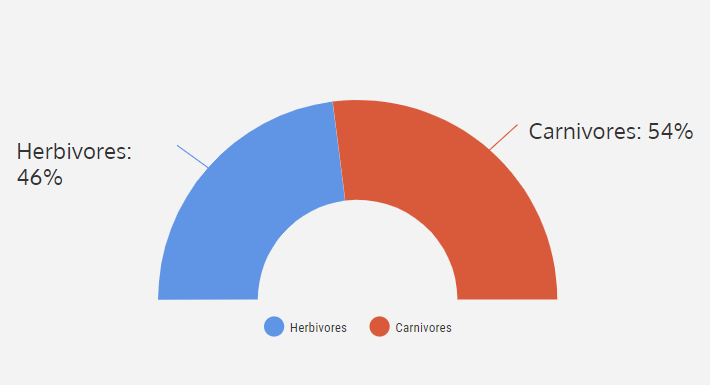

There are lots of different animals, but they fall broadly into two categories: carnivores and herbivores, the former having an annoying tendency to eat the latter, who don’t really appreciate it.

Herbivores and carnivores each have their own opinion leaders, who express themselves on the few TV channels and newspapers available. The herbivore party fights fiercely to ensure that herbivores have acceptable living conditions despite the threat of carnivores, while the carnivore party argues that they are necessary to the ecosystem and must eat.

Each side tries to squeeze voters out of the other by smoothing things over, and in the end we often end up with two very tight blocs around 50% of the vote.

When carnivores are in the majority, they tend to take measures that anger herbivores. In the next election, the herbivores are mobilized and put the carnivores back in power, who then take the opposite measures, and so on.

In the end, as we go back and forth, ideas that appeal to herbivores without displeasing carnivores are adopted, and vice versa. The result is a balance that more or less satisfies everyone.r

You’ll probably have recognized the “right/left” alternation that was the modus operandi of more or less all modern democracies until the 90s/2000s.

But then…

What happened?

Let’s return to the world of animals. In the 2000s, the number of media exploded: everyone wanted their own TV channel, THEIR own website, THEIR own community on THEIR own social network.

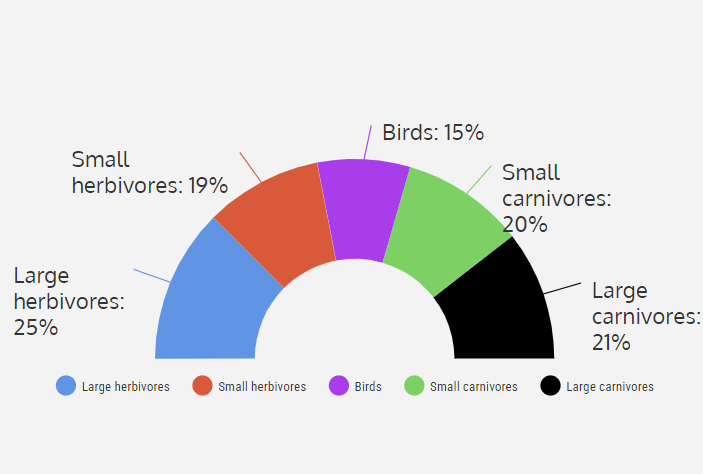

A rabbit is causing a stir on social networks: it points out that deforestation is threatening small animals to the benefit of large ones, and that small animals must join forces, whether they are carnivores or herbivores.

Birds, historically divided between the herbivore and carnivore parties, are coming together on social networks and deciding that they are finally numerous and special enough to have their own party and their own representatives to defend their rights.

In the end, the animals are divided into five main parties, all of which obtain between 15% and 25% of the vote in elections: small carnivores, large carnivores, small herbivores, large herbivores and birds.

And then you might say that’s no big deal. After all, whether there are 2 parties or 5, there are ideas that have a majority among the animals, and all we have to do is apply them. For example, all small animals and birds are in favor of stopping deforestation: with 3 parties against 5, they should have enough power to save the forests.

But no, in practice, in a representative democracy, it doesn’t work like that.

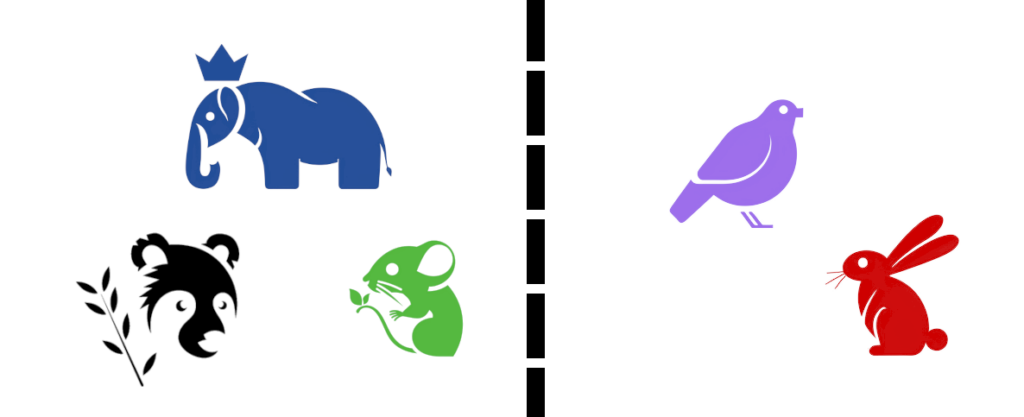

As the large herbivore party received the most votes, an elephant became president of the animals, but as he didn’t have a majority, he had to form an alliance with two other parties (the large carnivores and the small herbivores) to exercise power.

Given their membership of the animal government, and in order not to offend their allies the large animals, the small herbivores didn’t vote for the law against deforestation after all. Yet there was a majority of animals to support it. We’re left with an idea that, despite having a majority, will never go any further.

And it’s even the majority of ideas that will never be supported. Take, for example, an idea supported by 4 of the 5 parties. You’d think it would have absolutely no problem getting through our animal parliament. However, all it takes is for the only party opposed to the idea to be part of the governing coalition, and the idea will in fact never be supported.

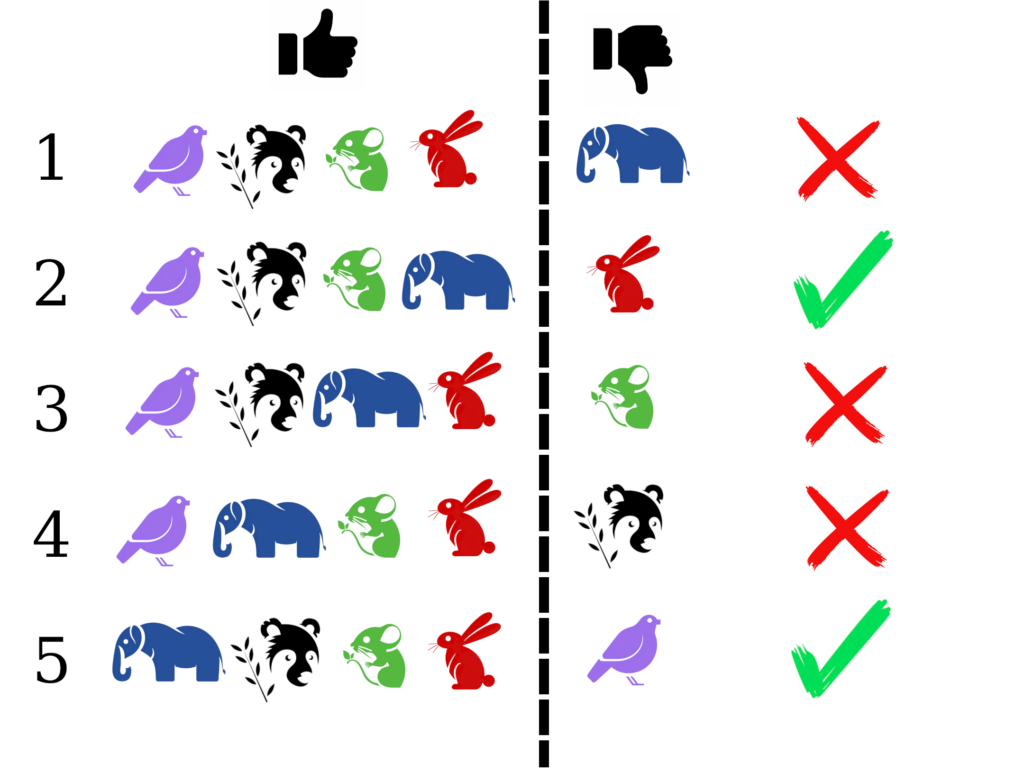

In the first example below (line number 1), a proposal is supported by 4 out of 5 parties, but the large herbivores (blue) do not support it. So as not to break up the government coalition, the allies (black and green) refuse to support the law. For a law to pass, all parties in the government must support it, which only happens in lines 2 and 5.

In this configuration, 60% of the majority ideas (supported by 4 out of 5 parties) may never be put into practice.

If we go a step further and study the ideas supported by 3 out of 5 parties, i.e. ideas that are in the majority, it’s even worse: 9 out of 10 majority ideas will never be put into practice.

The animal people as a whole are really starting to feel that they are not being listened to by their representatives.

The start of trouble

The small herbivores are furious: despite their presence in government, their representatives are doing nothing about deforestation.

Voters of large herbivores are disappointed: although they won the elections, only 10% of the electoral program is implemented, as their representatives have to come to an agreement with their allies in government.

Birds and small carnivores no longer expect anything from the government, which has never done anything for them. What’s more, they don’t have much hope, because they know that even if their representatives come to power, they too will have to build coalitions that won’t do much better than the current government.

There are variants of this world. There’s a world where, thanks to the electoral system, the large herbivores manage to retain power even with a minority of the votes, thus alienating almost all the other animals. There’s a world where primary elections select two sub-groups (one from among the carnivores, one from among the herbivores), so that as soon as the election is held, a majority of animals don’t feel truly represented by any candidate.

This world is our world: democracies in which decisions satisfy no one, countries that are ungovernable, citizens who are increasingly angry with their elected representatives, and more and more of whom believe that the very idea of democracy is obsolete.

And all this is not very reassuring.

So what do we do?

If we go back to the previous example, it’s clear that the problem isn’t so much that animals are divided into five groups. The problem is that their representatives, once organized into parties, are incapable of making the decisions that bring together the majority of animals.

The problem is not so much democracy, but representative democracy, or at least the way it exists today.

What the Baztille project is proposing is to repair representative democracy so that it can finally make the decisions that citizens want it to make. It’s about reversing the movement of anger and mistrust towards democracy, and making it functional and popular once again. It’s about showing that another path is possible alongside the current black scenario, which risks leading to catastrophe.

And how do you go about it? That’s the subject of the following article.